9.5 Theses on Art and Class by Ben Davis is one of the more interesting books I've read lately. Initially I was disappointed—I thought the book would be an expansion of his actual 9.5 theses, but instead it's a collection* of essays—some reprinted and expanded from other work—dealing with the intersection of art and radical politics, specifically Davis's own politics. He's a member or, or at least a close contact of, the International Socialist Organization. (The book is also published by Haymarket Books, the ISO publisher.) This, as we say in the dialectic business, is both a strength and a weakness.

The strength is that Davis is able to cut through enormous amounts of art crit bullshit. He mocks himself in his intro. When he first encountered Marxists (presumably ISO cadre) as opposed to post-Marxists or academic Marxists or other school people, he writes that he "explained that I was trying to develop a theory of how Kierkegaard's theory of the aesthetic aspect of seduction stood as a critique of the Hegelian master-slave dialectic, through a reading of pick-up tips from Maxim magazine." Davis got over that shit right away, thankfully. He's able to historicize art-crit ideologies without being sucked in by any of them, and he has one of the more cogent simultaneous critiques of both the outsider artist and the notion that "anything can be art" I've ever read. (Much of that's based on an earlier piece about wannabe insider Billy Pappas, which is online here.) He's also happy to do a little reportage. Very little, but more than most in his position. He writes, on the topic of postmodernism: "I asked two friends of mine, both working curators, if postmodernism mattered to their practice at all. The answer was an unambiguous no. 'It makes you sound like an undergrad.'"

![]()

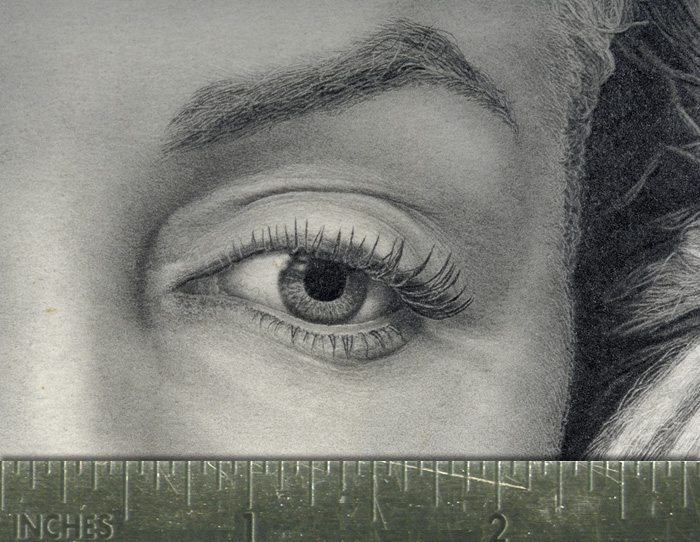

This extremely detailed drawing of a famous photo of Marilyn Monroe may seem like outsider art, but it isn't, because it's in dialogue with the art world. The craft of it, well that's a whole other issue...

Davis's work is also immensely readable, even quotable, and often humorous. Almost as though he's writing for an audience broader than a coterie of art world mandarins. ISO literature is the most readable and populist of the far-left milieu—I'm sure Davis knew how to write well before his encounter with the group, but I shudder to think of what would have happened to his rhetoric had he ended up in the orbit of the turgid goofballs of WSWS.org or *shudder* the Sparts. So, good for him! (This Davis article is apropos.)

The weakness is Little Lenin Disorder. In one chapter, Davis critiques the severe limitations of radical art collectives, which ape the form but not the content of worker collectives. (They can't, because art is a middle-class thing.) He also has many negative things to say about the Situationist International. They weren't so influential after all back during the events of May 1968, he tells us. Volumes can and should be written about how exactly the SI bobbed to the top of the revolutionary wave that summer, but Davis just punts. And he complains about artists who think their revolutionary activism should involve their art instead of, for example, joining Davis at his political meetings (presumably ISO meetings).

Occupy gets a bit of a drubbing too—they did good work, they got out on the streets, they spread worldwide, but where was the challenge to the state? Good question, but the answer can't be to point to the ISO or other vanguard or pre-vanguard formation and announce, "Your leaders have arrived!" (The answer, incidentally, is "Oakland.") And the vanguard party can't be because it hasn't been. Whether it's Occupy, or the anti-war movement of 2001-2003 or the anti-globalization movement of the 1990s, or the anti-war movement of the early 1990s, it's been very easy to find small groups who have all the answers and know the way forward. And it's been just as easy to find large groups of people who don't want to listen to them. Now of course there are many factors involved—in the US, the Democratic Party and its immense power to ride herd over people supposedly far to the left of electoral politics is a major one—but clearly one factor at this late date has to be the fundamental problem with vanguardist conceptions of revolutionary parties, and indeed the class formation of such small groups. (I remember that I met my first trust fund kids when I was a member of the ISO nearly twenty years ago. They form a semi-permanent leadership caste. Most of the rich kids I knew then are still in the group. The less rich ones from that era, with a couple of exceptions, are not.)

Or to put it more simply, when Davis points a finger at SI for only having a visible measure of influence over a massive general strike, and tsks tsks Occupy for an immense global movement that self-organized in a matter of weeks but then didn't strike a death blow to the world system, he's pointing four fingers back at himself and the ISO. "Yes yes, capitalism remains standing after all our work, Cde. Davis. And how many successful revolutions have you led again?" Luckily, Davis doesn't go on for too long.

Davis is on much stronger ground when it comes to political economy. He closely looks at the art market, how it influences art-making and art celebrity, and how dips and booms of the broader economy play a role in how artists, curators, museums, and buyers fit into the capitalist relations of production. A chapter on women in the arts is well-argued if not quite so radical as other essays. The essay on hipsters concludes, rationally, "that it is a waste to expel so much rhetorical ammo attacking what amounts to a a style." Indeed. He also introduced me to the term "ego-seum", thus saving me from having to read about it at the Forbes article just linked to (this being the art-politics equivalent of learning about sex from the streets, or worse, health class.) He also struggles mightily, and fruitfully, with the question of the politics of political aesthetic/aesthetically political, demonstrating and declaring at once that "[d]isentangling what is aesthetically affecting from what is politically effective is one of the vital tasks of criticism. Muddling the two can only do a disservice to both." And that should be the theme to Davis's next essay collection.

*Googling suggests that the book may have had the subtitle and Other Writings. The publisher should have stuck with that.

The strength is that Davis is able to cut through enormous amounts of art crit bullshit. He mocks himself in his intro. When he first encountered Marxists (presumably ISO cadre) as opposed to post-Marxists or academic Marxists or other school people, he writes that he "explained that I was trying to develop a theory of how Kierkegaard's theory of the aesthetic aspect of seduction stood as a critique of the Hegelian master-slave dialectic, through a reading of pick-up tips from Maxim magazine." Davis got over that shit right away, thankfully. He's able to historicize art-crit ideologies without being sucked in by any of them, and he has one of the more cogent simultaneous critiques of both the outsider artist and the notion that "anything can be art" I've ever read. (Much of that's based on an earlier piece about wannabe insider Billy Pappas, which is online here.) He's also happy to do a little reportage. Very little, but more than most in his position. He writes, on the topic of postmodernism: "I asked two friends of mine, both working curators, if postmodernism mattered to their practice at all. The answer was an unambiguous no. 'It makes you sound like an undergrad.'"

This extremely detailed drawing of a famous photo of Marilyn Monroe may seem like outsider art, but it isn't, because it's in dialogue with the art world. The craft of it, well that's a whole other issue...

Davis's work is also immensely readable, even quotable, and often humorous. Almost as though he's writing for an audience broader than a coterie of art world mandarins. ISO literature is the most readable and populist of the far-left milieu—I'm sure Davis knew how to write well before his encounter with the group, but I shudder to think of what would have happened to his rhetoric had he ended up in the orbit of the turgid goofballs of WSWS.org or *shudder* the Sparts. So, good for him! (This Davis article is apropos.)

The weakness is Little Lenin Disorder. In one chapter, Davis critiques the severe limitations of radical art collectives, which ape the form but not the content of worker collectives. (They can't, because art is a middle-class thing.) He also has many negative things to say about the Situationist International. They weren't so influential after all back during the events of May 1968, he tells us. Volumes can and should be written about how exactly the SI bobbed to the top of the revolutionary wave that summer, but Davis just punts. And he complains about artists who think their revolutionary activism should involve their art instead of, for example, joining Davis at his political meetings (presumably ISO meetings).

Occupy gets a bit of a drubbing too—they did good work, they got out on the streets, they spread worldwide, but where was the challenge to the state? Good question, but the answer can't be to point to the ISO or other vanguard or pre-vanguard formation and announce, "Your leaders have arrived!" (The answer, incidentally, is "Oakland.") And the vanguard party can't be because it hasn't been. Whether it's Occupy, or the anti-war movement of 2001-2003 or the anti-globalization movement of the 1990s, or the anti-war movement of the early 1990s, it's been very easy to find small groups who have all the answers and know the way forward. And it's been just as easy to find large groups of people who don't want to listen to them. Now of course there are many factors involved—in the US, the Democratic Party and its immense power to ride herd over people supposedly far to the left of electoral politics is a major one—but clearly one factor at this late date has to be the fundamental problem with vanguardist conceptions of revolutionary parties, and indeed the class formation of such small groups. (I remember that I met my first trust fund kids when I was a member of the ISO nearly twenty years ago. They form a semi-permanent leadership caste. Most of the rich kids I knew then are still in the group. The less rich ones from that era, with a couple of exceptions, are not.)

Or to put it more simply, when Davis points a finger at SI for only having a visible measure of influence over a massive general strike, and tsks tsks Occupy for an immense global movement that self-organized in a matter of weeks but then didn't strike a death blow to the world system, he's pointing four fingers back at himself and the ISO. "Yes yes, capitalism remains standing after all our work, Cde. Davis. And how many successful revolutions have you led again?" Luckily, Davis doesn't go on for too long.

Davis is on much stronger ground when it comes to political economy. He closely looks at the art market, how it influences art-making and art celebrity, and how dips and booms of the broader economy play a role in how artists, curators, museums, and buyers fit into the capitalist relations of production. A chapter on women in the arts is well-argued if not quite so radical as other essays. The essay on hipsters concludes, rationally, "that it is a waste to expel so much rhetorical ammo attacking what amounts to a a style." Indeed. He also introduced me to the term "ego-seum", thus saving me from having to read about it at the Forbes article just linked to (this being the art-politics equivalent of learning about sex from the streets, or worse, health class.) He also struggles mightily, and fruitfully, with the question of the politics of political aesthetic/aesthetically political, demonstrating and declaring at once that "[d]isentangling what is aesthetically affecting from what is politically effective is one of the vital tasks of criticism. Muddling the two can only do a disservice to both." And that should be the theme to Davis's next essay collection.

*Googling suggests that the book may have had the subtitle and Other Writings. The publisher should have stuck with that.